Technically, the new reforms are a masterpiece to constrict the banking industry. Unfortunately, they do not take into account an essential element, the ability of banks to improve their service to the economy, which, in my opinion, is the only guarantee of a long-term survival of the banking industry.

Now, as we shall see, two forces are undermining the ability of banks to fulfill their economic role: They are losing their ability to measure risks properly (object of this article), and they must carry a disproportionately large share of the capital available in the economy (object of next month’s article).

Simplistic risk models

Focusing on normative measures of risk (Pillar 1) or subjective ones (stress tests) has led banks to gradually erode their ability to properly measure risk, and thus lose what makes their purpose in the economy.

Indeed, the economic value of banks is largely due to their ability to channel available savings to actors who need funding; thus the ability of banks to assess the risk of default is at the heart of their rationale.

But for years, regulators have encouraged banks to use a model for measuring risk (Pillar 1) unanimously recognized for its simplistic assumptions. Let us recall a few:

- The main model, for credit risk, largely ignores concentration effects. It is a so-called called "one factor" model, that is to say, it measures potential losses on the basis of a single risk factor, i.e. the probability of default of the borrower. This model ignores other important factors such as belonging to a group of customers, being part of an industry sector or a geographic area. This oversimplification results from the objective of regulators to measure risks in a way that is both analytical and additive. Unfortunately, the business model of banks rests for a large part upon the diversification of risks, with the consequential hazard of excessive concentration. The regulatory model does estimate a possible contagion of default through an "asset correlation” factor, but this depends only upon the rating of the borrower. This approach has shown its limits during the recent crisis when contagion in the financial sector was found higher than expected by the model. In response, when publishing Basel 3, the regulator has uniformly increased by 25% the asset correlation coefficient for large financial institutions. Can do better.

- The measure of sovereign risk is also a concern. Against the advice of the Basel Committee, the European Union has authorized supervisors to allow IRB banks to maintain the standard approach for their sovereign exposures ... and in this approach to provide a zero weighting to sovereign exposures issued in the currency of the issuing country ... or any currency of an EU member country. By removing the sovereign risk with the stroke of a pen, the European regulator has obviously undermined its credibility.

- The risk associated with the maturity of the exposures is limited to 5 years, which obviously favors very long exposures as these offer a better profitability without any apparent penalty in terms of regulatory capital. The current situation of low interest rates favors long loans and reinforces this aberration.

- Also, many risks are neglected, funding risk, banking book interest rate risk, the cost of prepayments, structural foreign exchange risk, etc.

Perverted internal models

Pillar 1 is thus in line with its original purpose: To provide a simple normative measure that was not originally intended to be part of the internal management of the bank.

For this, the bank is supposed to use its own internal models (Pillar 2). But these were gradually corrupted because, contrary to the spirit of Pillar 2, their results are cherry-picked by supervisors to adjust the minimum capital requirements imposed on banks on an individual basis (

These internal models have historically been developed by banks to provide the very best assessment of risks they could come up with. In fact, this expertise is at the heart of the banking business model. So these models have existed long before regulators started to require them. Unfortunately, since then, they have been gradually damaged to reduce the apparent need for regulatory capital.

For example, until 2008-2009, all banks had in their Pillar 2 a “business risk” to account for potential changes in income not explained by the traditional credit, market and operational risks. Business risk is usually high for financial services activities such as asset management or merger and acquisition services. But as its capitalization in pillar 2 did not particularly attract the attention of the regulator, it soon disappeared. As for the business risk itself, it remains of course, and often unchecked.

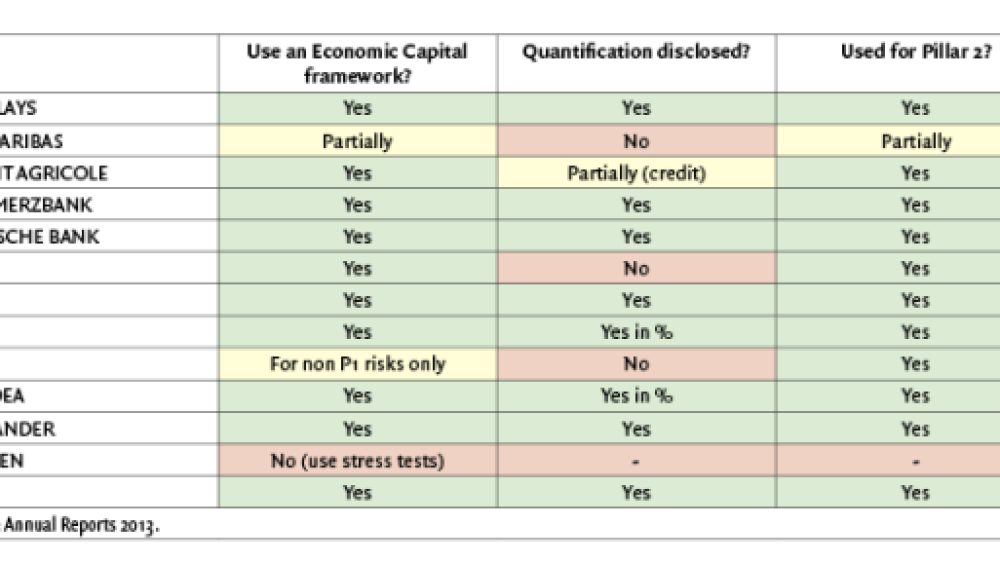

In the same vein, internal statistical approaches for measuring risks such as Economic Capital live an existential crisis, especially in France. The concept of Economic Capital has completely disappeared from the annual reports of the Société Générale or Natixis for example, and it is reduced to its simplest expression in those of BNP Paribas and BPCE.

What about Economic Capital?

In these institutions and in others, Economic Capital is gradually replaced by more or less severe stress tests, which are more holistic, intuitive, understandable by the regulators ... and also more easily "calibrated" to deliver the desired results. Indeed, assessing the impact of a hypothetical economic crisis on risk parameters such as PD, LGD, etc. is a very delicate matter and leads to heavy approximations. As for the macroeconomic stress scenario used, it is obviously subjective, even if it comes from the highest authorities. For example, the recent EBA stress test unrolled a hypothetical future crisis in the United States; In Europe, no crisis in view...

It should be mentioned that outside of France, many leading European Financial Institutions continue to use an Economic Capital framework for their Pillar 2, and to disclose the results in their annual

Still, some critics of statistical approaches are justified, in particular that "the past is not a proof of the future." But this overlooks its two core strengths: First, the alternative to the statistical approach consists of the stress tests, which are highly subjective and whose predictive power is low; Secondly, the objective of measuring risks is not to have a perfect assessment in absolute terms, but to have a measure slightly better than the competition’s. For this, collecting and using the data of past events is essential; this is also known as not having a short memory.

New actors, less regulated

So, facing a regulatory pressure that promotes the use of models that provide too simplistic measures of risk and leads to damage the historical internal models, banks are currently making choices that are leading them to lose gradually their ability to assess risks properly!

What are the consequences? First, a standardization of risk measurement, which reduces competition; and less competition means higher prices and thus a worsening service to the economy. Also, the risk measurement biases induced by the regulation push banks to finance the States instead of the productive economy.

It can also be pinpointed that the biodiversity of the banking system is shrinking: This has the effect of eliminating credit supplies to large sectors of the economy, such as project financing or local authorities financing, even though for the latter public mechanisms were promptly worked out, funded by taxpayers of course!

Finally, banks' ability to innovate and to serve new markets is almost nonexistent. Only new players, less sensitive to regulatory constraints, can develop “peer-to-peer”, “crowd funding” and other new financing techniques that are growing in the cracks of the banking system.

Altogether, the unexpected consequences of the regulation are quite dramatic and carry the seeds of a withering of the future of the banking system, and its replacement by new players closer to markets and less regulated.

Will strengthening bank’s capital save the system? If not, what other solutions could be considered? To be continued...

![[Web Only] Tarifs bancaires : les banques amortissent l’inflation [Web Only] Tarifs bancaires : les banques amortissent l’inflation](http://www.revue-banque.fr/binrepository/480x320/0c0/0d0/none/9739565/MEBW/gettyimages-968963256-frais-bancaires_221-3514277_20240417171729.jpg)